Forgetting Yosef…Again?

By Rabbi Shaya Hauptman

The story of Jewish exile doesn’t begin with chains or forced labor. It begins with forgetting. The Torah tells us that a new Pharaoh arose in Egypt who “did not know Yosef,” and that phrasing is more meaningful than it appears at first glance. Yosef wasn’t some distant historical figure whose contributions had faded with time. He was the one who saved Egypt from total collapse, navigated a global famine, centralized the world’s wealth into Egypt, and turned it into the dominant superpower of its age. The country’s economic stability, political strength, and global relevance were all tied directly to him.

Forgetting Yosef wasn’t ignorance. Rashi explains that it was a choice. Gratitude stood in the way of exploitation, and memory made cruelty harder to justify. Once Yosef was erased from the national story, the Jews could be recast as a threat, and eventually as property. The oppression of the Jewish people in Egypt didn’t emerge from nowhere. It was enabled by contempt, betrayal, and a deliberate rewriting of history.

That pattern doesn’t belong to ancient Egypt. It’s one of the most common patterns in Jewish history; it just began then.

Fast-forward to the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, as the civil rights movement gained momentum. Entire groups of people had been excluded from basic protections and opportunities, and the country was finally being forced to confront its own contradictions. Jews were not incidental to this movement. They were among its most active forces, both publicly and behind the scenes, often at personal and professional risk.

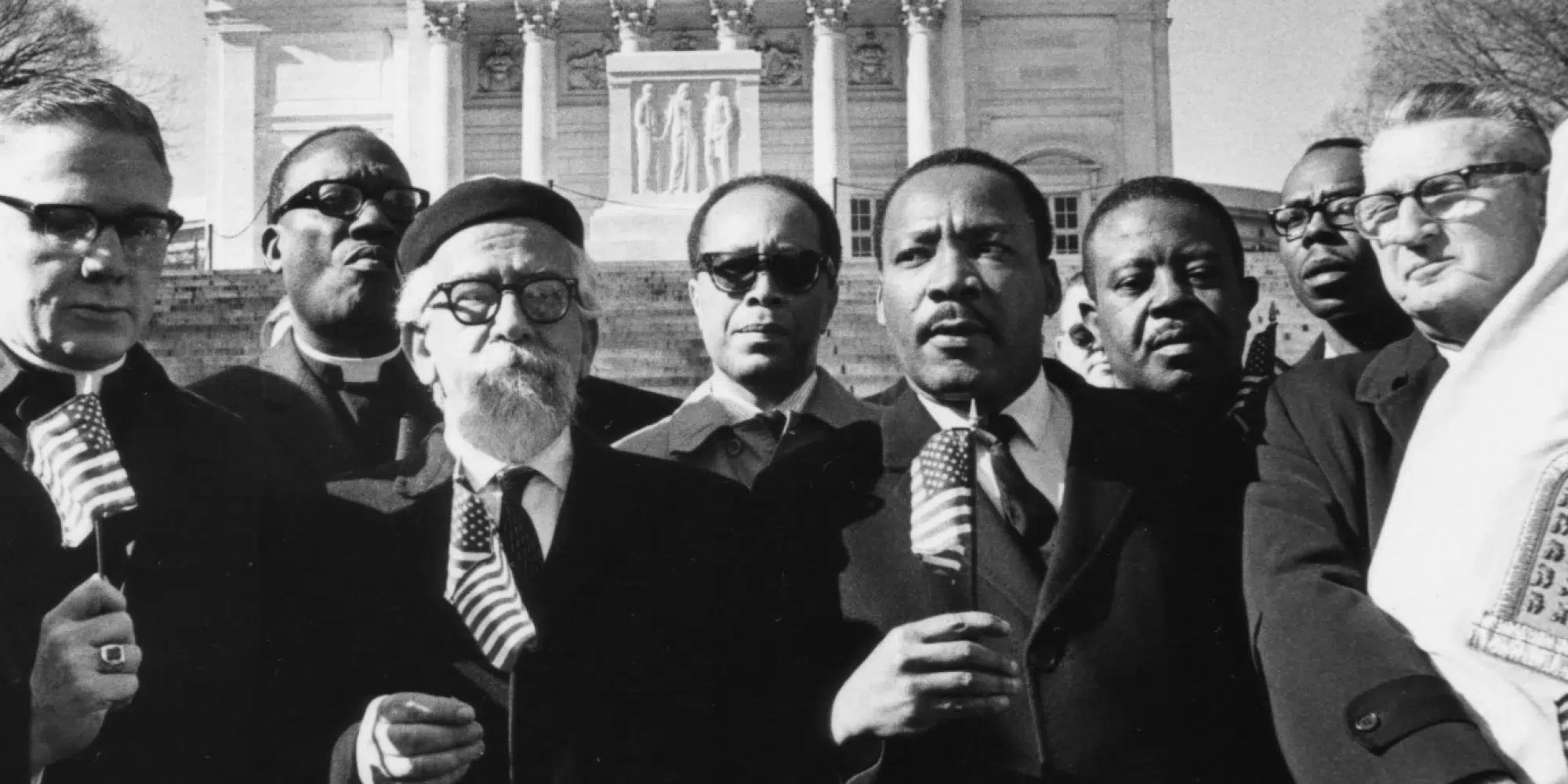

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched alongside Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma and famously said that his legs were praying. Jewish lawyers filled the ranks of civil rights legal teams. Jewish academics helped shape the constitutional and moral arguments that expanded protections for minorities. Jewish donors funded voter registration drives in the South. Jewish journalists documented abuses others ignored. This wasn’t political or sociological posturing. It was sustained, principled involvement, rooted in a long memory of what it means to live without protection, and a sense that Jews have responsibilities beyond themselves.

Many Jews paid for that commitment, but the sense of responsibility didn’t waver. Jews understood, perhaps more intuitively than most, what happens when a society decides that certain lives matter less and certain rights are conditional.

Now move ahead another fifty years.

The United States has been enriched in countless ways by its Jewish population, culturally, intellectually, economically, and morally. Its position on the world stage, particularly in the Middle East, has been reinforced through its alliance with Israel and the Jewish people’s unwavering commitment to democratic values. And yet, once again, we’re watching Yosef being forgotten.

In states like California, Michigan, Illinois, New York, and others, candidates in upcoming elections are being publicly vetted by advocacy and donor groups and asked to affirm that Israel is a genocidal state as a condition for legitimacy. This isn’t happening on the margins. It’s taking place in candidate forums, questionnaires, and activist-run debates. Some candidates comply immediately. Others hesitate and are pressured until they do. The message is clear either way: alignment with this framing is now treated as a moral prerequisite.

At the same time, there is a growing list of sitting elected officials across multiple states who have already adopted this language, publicly condemning Israel while insisting that their position has nothing to do with antisemitism. We’re told, repeatedly, that this isn’t hatred of Jews, just opposition to Israeli policy. That it’s not antisemitic, just pro-Palestinian. That it’s not hostility toward a people, only concern for human rights.

That framing collapses under even minimal scrutiny.

Israel isn’t an abstract political entity floating free from the Jewish people. It represents the collective expression of Jewish self-determination after millennia of statelessness, persecution, and exile. To single out the Jewish nation for moral condemnation while denying its right to defend itself against an existential threat isn’t a neutral human rights stance. It’s the modern language of antisemitism dressed up in moral vocabulary that makes it more socially acceptable.

There is no people on earth whose historical record on human rights advocacy is stronger than that of the Jews, whether in exile or in sovereignty. The same people now accused of genocide are the ones who marched for civil rights, built legal frameworks for equality, advanced medicine, science, and ethics, and consistently argued that human dignity is not negotiable. To suggest that Jews suddenly abandoned those values the moment they gained a state defies history, logic, and boots-on-the-ground facts.

This moment feels bleak, but it isn’t new. The Jewish people entered Egypt as a family of seventy and emerged generations later as a nation, enslaved precisely because they had grown strong and remained distinct. That oppression led directly to the Exodus. From there, the pattern repeated across history, through superpowers like Babylon, Persia, Rome, Greece, Spain, and eventually, the rest of Europe, across continents and centuries. Each era found its own justification. Each claimed moral high ground. Each insisted that the Jews were the problem.

And yet, we remain.

In his essay Concerning the Jews, Mark Twain marveled at this persistence. He listed the great civilizations that rose, dominated the world, and vanished, while the Jewish people endured, unchanged in vitality and contribution. He asked the obvious question: What is the secret of Jewish immortality?

We know the answer. It isn’t power, numbers, or circumstance. It’s the covenant. A shared promise that we wouldn’t abandon G-d, and that He wouldn’t abandon us. That promise has carried us through every exile and every threat, and it continues to do so now. Which is why we Jews continue to speak, to advocate, and to show up for others, even when it’s uncomfortable or unpopular. Not because it’s safe or earns approval, but because it’s who we are – it’s in our DNA.

That same instinct hasn’t disappeared. It’s how Jews have consistently responded whenever we’ve been granted stability, influence, or safety: by turning outward and taking responsibility for those who can’t protect themselves. At The Ark, that commitment shows up every day through client advocacy, supporting the vulnerable, and restoring dignity to the people society often overlooks, not as a slogan or a political stance, but as a lived expression of the same values that have guided the Jewish people from the moment of its inception.

Pharaoh forgot Yosef. Many nations have since followed suit. History suggests others will again. But the Jewish people are still here, and we’ll continue to be a light unto the nations, not because the world always welcomes it, but because that’s who we are.